Understanding loss and grief in racialized communities as a result of COVID-19

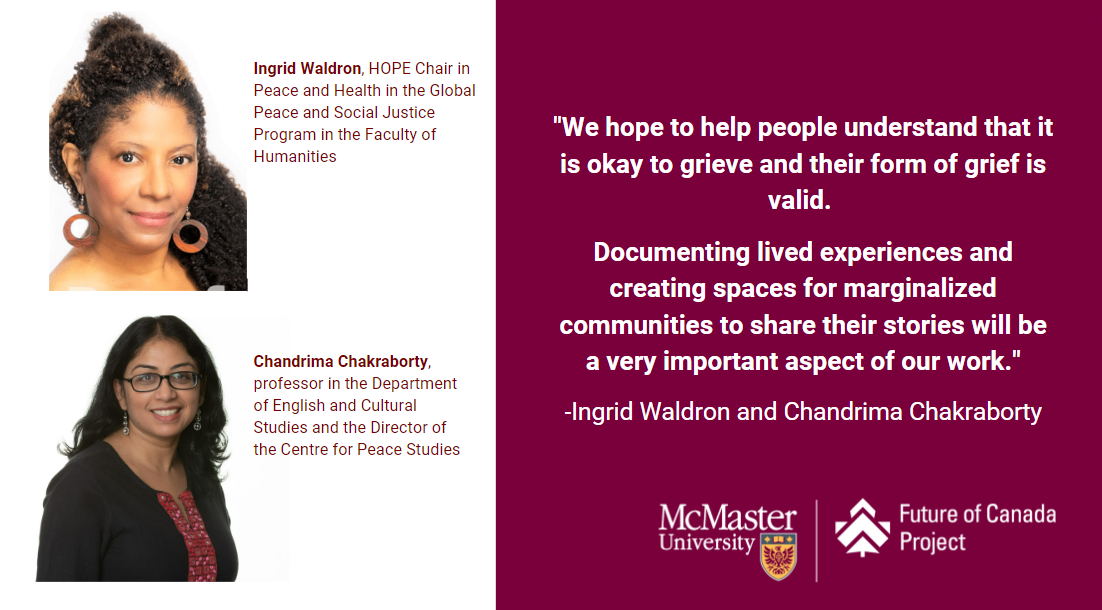

Ingrid Waldron, HOPE Chair in Peace and Health in the Global Peace and Social Justice Program and Chandrima Chakraborty, professor in the Department of English and Cultural Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and the Director of the Centre for Peace Studies are the principal investigators of Future of Canada Project “COVID-19 in racialized communities in the Greater Toronto Area: experiences and conceptualizations of loss”.

We recently spoke with Ingrid Waldron about the project and how centering the voices and experiences of marginalized populations can lead to better public health responses.

We know that South Asian and Black communities were hit hardest by COVID in terms of infection rates. There is, of course, a lot of loss and grief associated with illness and death resulting from these higher rates of infection, but how is the loss and grief that your project is exploring different?

A lot of COVID studies are focused on the physical impacts of COVID like death and illness or the grief and loss directly associated with this death and illness. This is important research, but we wanted to come at things from another angle that has to do with loss and grief on a different level.

We want to look at loss, not just in the context of something like losing a family member to COVID, but the kind of loss that is less tangible—the loss of friendships, the lack of safety and security people feel, and the lack of comfort some people now have in social settings as a result of COVID.

How will this project benefit the people in the communities that you are researching?

My Co-Principal Investigator on this project, Chandrima Chakraborty, and I will work with 100 participants—50 people from the Black community and 50 people from the South Asian community in the GTHA.

We are going to partner with groups that already have inroads into these communities such as the South Asian Task Force and the Black Scientists’ Task Force On Vaccine Equity. These communities can feel over-researched so ensuring that there is value for the individuals we are working with is really important.

We are going to be sharing our findings via a website that we hope will serve as a resource for the participants in this project. The site will serve as a storytelling blog as well as a place for participants to find mental health resources and other community supports.

The storytelling aspect of the website will be an important way for people to have their stories heard and for people to realize that they are not alone in their experiences of loss and grief. I’m hoping it will create a sense of connection and will give people the space to share their grief.

Grief and loss can be sensitive subjects—how will you approach these topics with the project participants?

Since we will be using narrative methodology, which will involve in depth interviews where individuals will be sharing sensitive and personal details about their experiences, we have to be prepared to support them as needed and ensure we are not pushing people to tell their stories in a way that could be harmful to them.

Our research assistants will be trained to navigate these interviews with care and will have a list of resources ready for those participants who want to use them.

On the website, we will include links to mental health resources and other supports too such as settlement organizations. A lot of racialized people don’t like to access formal mental health services because of the stigma attached to mental illness, but if you go to a settlement agency where you may be accessing other services, you are still able to talk to someone who understands your situation and potentially get your needs met that way.

When people have the space to get things off their chest, it can do wonders.

What impact do you hope this research will have?

In order to continue responding and recovering from the pandemic, it is critical to acknowledge the differential impacts of COVID-19 on racialized Canadians and ensure their voices and experiences are integrated into health system decisions going forward.

Through this project, we want to work our findings into health policy on a broad scale as well as on an individual health practitioner level.

Some health professionals may not be culturally competent and may not realize that grief shows up differently in different communities.

We know that South Asian and Black communities are not homogenous. There are different languages, cultures and religions at play. We are asking, how does each group present grief and how do they present loss? It might be in very distinct ways because of the many intersectional identities.

Knowing this, how do we enable health professionals to develop cultural competency? How do we ask these professionals to recognize the different ways in which people conceptualize and demonstrate or show grief and loss in their lives? And, in addition, how do they manage their loss and grief? What are their struggles in accessing help?

We also want to look at things more broadly and recognize that it isn’t only the responsibility of health professionals to be culturally competent—we also have to develop health policy that captures the way illness is conceptualized.

It is important for health and policy professionals to understand how grief is being presented in these communities, because if they miss it or they don’t take a person’s grief seriously, this can do a lot of damage to someone’s health as they might not connect them with the services they need.

You are the HOPE Chair in Peace and Health in the Global Peace and Social Justice Program and your co-principal investigator on this project, Chandrima Chakraborty is the Director for the Centre of Peace Studies. How have peace studies led you both to this work?

Both Chandrima and I are interested in how peace can be achieved through better health.

Exploring physical violence is often a focus of peace studies, but through this project Chandrima and I are both interested in studying the more subtle, systemic forms of violence that show up in society. This includes how policies and decisions around health care impact people’s well-being—particularly the lives of racialized people who do not feel heard or seen by those making decisions that impact their everyday lives.

What aspect of this project are you most looking forward to?

I’ve done a lot of studies on mental illness but looking at loss and grief in this light is unlike anything I have done before. I haven’t heard of any other studies that are looking at grief and loss resulting from COVID in this way, and certainly not in these communities in Canada, so I am excited about what we will find.

Future of Canada Project Profile